If you go to a Forever 21 location two months in a row, odds are that practically nothing about the clothing selection will look the same. Forever 21 played a massive role in popularizing fast fashion, and as Green America’s Toxic Textiles report recently found, workers and the Earth pay a massive price for these seasonal looks, exposing workers to hazardous conditions and polluting our water, soil, and air.

Between 2000 and 2015, clothing production almost doubled, from about 50 billion pieces a year to over 100 billion pieces a year. In addition, the amount of clothing Americans dispose of annually has almost tripled during that time. Green America recently investigated sustainability practices in the clothing industry, revealing how the push towards fast fashion has resulted in significant carbon emissions and environmental degradation. Green America’s labor justice campaigns manager Charlotte Tate says it is crucial for individuals to know exactly what toxic chemicals could be in their clothing, especially given the lack of transparency in the industry.

“Currently, companies are deciding what chemicals are okay for consumers to be exposed to and at what levels, and companies are making those same decisions for workers,” says Tate. “Information about what chemicals are being used at all tiers of the supply chains must be made public, so that the deciding power is not only with companies trying to maximize profits.”

Textile producers and clothing companies not only largely fail to commit to environmental sustainability, their increased activity threatens the water supply and soil quality, while also using materials that present dangers for their labor force.

Further, less than one percent of the resources used to make clothing are captured and reused to create new clothing. Although many people donate their unwanted clothing, many of those clothes go unused after donation, eventually also becoming trash. This failure to create a cyclical system of clothing reuse means that most textile sales are of new products, accelerating the release of chemicals.

Water Use and Pollution

Water pollution is the most notable impact of clothing production, with around 20 percent of global industrial water pollution traceable directly back to the textiles industry. The pollution is multifaceted and affects all aspects of water ecosystems, from chemical contamination of drinking water to the spread

of microplastics into waterways around the world.

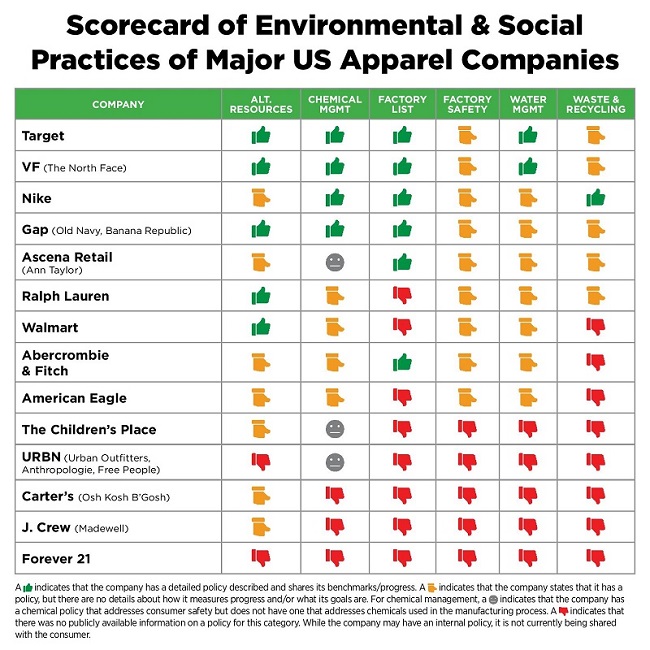

Target, VF (which owns The North Face and Jansport), Nike, and Gap have all introduced Manufacturing Restricted Substances Lists (MRSL) and Restricted Substances Lists (RSL) to eliminate the use of some chemicals that harm workers and consumers. These lists are an excellent first step, with a MRSL restraining what can be used in the manufacturing process and a RSL dictating what can be in the final product. The reality is that the vast majority of chemical exposure is to workers—some exposure occurs when consumers get the clothes, but much more to the worker.

“Companies need to work with their suppliers to ensure that the MRSL is being implemented appropriately,” Tate notes. “Companies need to be paying enough for their products so that the supplier is able to implement the MRSL, and all apparel companies should come together and agree on one complete and holistic MRSL and RSL—raising industry standards across the board.”

The impacts of chemicals banned in the final product but allowed in the manufacturing process, like dyes, polyfluorinated chemicals, and flame retardants, are striking. In China, 70 percent of the rivers and lakes are polluted, and in Bangladesh, the Buriganga River is so polluted with toxic chemicals and heavy metals prevalent in the leather tanning industry that it can no longer sustain aquatic life.

Even alternatives to conventional textile production cause environmental degradation. Organic cotton is grown without toxic chemicals, but unless the clothes are certified under GOTS, bluesign®, or Oeko-Tex certifications, toxic chemicals may be added in the textile production process.

Green America’s Toxic Textiles report also found that the bamboo used in some shirts involves a more chemical-intensive process to make the material soft. Like bamboo, rayon fabric (and its variant, lyocell) is derived from raw materials in wood pulp, which go through energy- and chemical-intensive processes with to become a semi-synthetic material. The chemicals used generally aren’t recaptured but instead are released into waterways.

Cotton is among the most water intensive crops and both organic and conventional clothing manufacturers consume enormous amounts in both farming and textile production. An astonishing 2,700 liters of water are required to grow the cotton needed to make a single t-shirt. These watering practices are especially harmful in the primary cotton-growing countries as they often face water scarcity but need to continue cotton production to maintain their economy. In Kyrgyzstan, where water is both contaminated and scarce, many civilians have no access to clean drinking water, even as cotton producers use thousands of liters.

Microplastics

Unfortunately, chemicals aren’t the only harmful substances polluting water as a result of the textile industry. At every step of the manufacturing process, including after the product reaches the consumer, microplastics can be released into our waterways. When synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon, and acrylic break down, they release microfibers, another form of microplastic.

The global spread of microplastics was discovered relatively recently but is a cause for major concern, both for the uncertain health effects on humans and the deaths of aquatic animals that have consumed these microfibers.

When washing clothes using materials prone to shedding microfibers, each load releases as many as 700,000 microfibers into the water. These tiny plastics spread quickly, and when they accumulate in the digestive systems of oceanic animals, they can be fatal. With their health effects largely unknown but potentially hazardous, this spread is concerning.

“You and I and everybody else on earth is drinking and bleeding microfibers,” says Dimitri Deheyn, a marine biology researcher at University of California in San Diego, who spoke about microfibers at the Unveiling Fashion conference in Washington, DC, in September 2019. “There are no studies whatsoever on the effect of microfibers made of plastic on public health, […] we’re just starting to look at this toxic aspect of microfibers.”

But contamination is not the only negative effect on water that occurs during the textile manufacturing process.

Air, Soil and Agriculture

Many of the same chemicals that contaminate water end up in the soil as well, affecting agriculture as more land becomes less arable. Additionally, irresponsible sourcing practices for the raw materials also threatens endangered ecosystems, including rainforests and heavily deforested areas.

This impacts even supposedly sustainable materials, including rayon, a common silk substitute. Rayon is made with wood pulp, which is regularly sourced from endangered or protected forests. Worse, 60 to 70 percent of the wood pulp is lost in the process. As a result, rayon production fuels the deforestation crisis and requires vast amounts of wood for relatively little fabric.

Wood pulp harvesting, particularly when done in endangered forests, accelerates deforestation, which has wide-reaching effects on biodiversity. It is unfortunately part of the production process for rayon, viscose, and lyocell. Removed trees can no longer enrich the soil and air, negatively affecting the forest ecology. Degradation also occurs at the manufacturing stage; Rayon manufacturing factories in China contribute to severe air and water pollution, and residential areas near factories have reported dangerous levels of carbon disulfide, a chemical that can cause insanity, Parkinsonism, and birth defects.

Conventional cotton is very likely to be grown from genetically modified seeds, which often increase the use of pesticides on the crop. Cotton production has also increased over the past few years, as an increase in clothing demand drives farmers to extreme measures to keep up. The scale means farmers are prevented from planting a more diverse set of crops, which could help maintain the integrity of the soil and which also require less water. See our story on regenerative cotton to read more about regenerative and conventional cotton.

Exposing Workers to Toxic Chemicals

With sweatshop labor notably prominent in the textile industry, worker safety is rarely a priority in textile factories. However, increased textile production and the widespread use of chemicals in many developed countries also threatens these workers.

Polyester textiles, used in 55 percent of all clothing production, rely on the use of heavy metals, like antimony, a possible carcinogen, as well as known carcinogens, like cadmium and lead. Research from the National Institutes of Health shows that occupational exposure to antimony can cause respiratory, skin, and gastrointestinal symptoms, and may even cause cancer. Too often, factory workers who may encounter such toxic materials are not notified about safety procedures or given proper equipment to reduce exposure.

It’s not only polyester—nearly every textile material undergoes the wet processing phase of production, where dyeing and chemical processing takes place. Too often, workers lack proper protection. In countries with these wet processing factories, like China and Bangladesh, officials don’t enforce the need to inform workers about the dangers of the chemicals or provide them adequate safety equipment. Wet processing plants are far down the supply chain from the companies and get less attention as a result.

Companies can help protect their workers by restricting the types of chemicals used in their clothing, but until that occurs, workers are threatened at every step of the process. This starts with the field workers, endangered by the cocktail of pesticides sprayed on conventional cotton crops.

“Chemicals used to produce clothing can disrupt hormone systems, harm liver health, or cause cancer,” says Tate. “Brands have a responsibility to ensure that workers in their supply chain have a safe and healthy workplace and that their basic right to health is not violated by the chemicals used to make clothes.”

Consumer Activism as a Solution

For three decades, Green America has been active in greening the apparel industry, by pushing companies like Nike, Hanes, and Gap, to address sweatshop labor in their supply chains.

Transparency is the first step in creating a safer textile industry. As consumers learn about key issues, they can begin to protect themselves, workers, and the environment from extreme pollution. The first and most important thing for people to do is reduce their consumption of new clothes. Even the alternatives to conventional textiles aren’t without their own concerns. As Green America’s report makes clear, there are no true leaders in this field, only relative successes.

“Brands are great at making big, vague commitments that don’t deliver the implied impact,” says Tate. “And on top of this, a majority of the commitments are voluntary, meaning there are no repercussions if the company does not meet its commitment.”

Green America and our members have a large role to play. With workers often unable to advocate for themselves in factories, consumer pressure may be the best way to advocate for ethical and environmentally sustainable textile production.

Other organizations have also joined the push for more responsible textile production, as our ally Stand.earth pressures Levi’s to put in place firm climate commitments for their overseas production facilities.

“Consumers have a lot of power with the textile industry. Millennial and Gen Z consumers especially are shifting their purchasing to companies that treat their workers well, use fewer toxic chemicals, and create durable clothes,” says Todd Larsen, Green America’s executive co-director for consumer and corporate engagement. “This shift in purchasing has drastically reduced sales at fast fashion companies like Forever 21, which just declared bankruptcy.”

Kids clothier Carter’s (which also owns OshKosh B’gosh), is a major polluter, but their defensive response to questions about their process shows how these companies want to be seen as environmentally friendly and how they will fight to protect their image. Since the launch of Green America’s campaign to pressure Carter’s into improving their supply chain, almost 7,000 concerned people have signed on.

The systematic failure of textile producers and clothing companies to protect their workers and the environment outlined in the Green America report shows the necessity of this action. And as Larsen notes, customers can make their voices heard.

“This is the same approach we used to address toxins in the electronics sector, and it works.”