On the rolling hills of Southeastern Washington state, Ariel Zakarison drives a tractor over her family’s farm, which, at 600 acres, is a relatively small farm on the scale of US agriculture. But her family’s land isn’t trying to be like every other farm. The Zakarisons use their land on the Palouse, a region that includes parts of Washington, Idaho, and Oregon in support of other small farmers.

Thirty-six-year-old Ariel and her mother, Sheryl Hagen-Zakarison, use their farm in support of their mission to spread the word and benefits of regenerative agriculture, and help neighboring small farms stay alive.

How They Feed the Land and Those Who Live on It

The family grows small grains including triticale (a hybrid of wheat and rye), winter peas, barley, wheat, and a rotation of cover crops. All those small grains get ground up into animal feed and sold to local farmers under the company name Zakarison Partnership Feed. The grains are grown with soil health in mind—using regenerative practices—which create nutrient-dense feeds for poultry, hogs, and ruminants. They also work to start important conversations.

“A lot of folks, especially in this area where there’s a lot of conventional farming, view soil as a substrate, just something that we put seeds into and chemicals onto,” Zakarison says.

She explains that over time, the nutrient density of crops grown on heavily chemically treated soil diminishes, and beneficial bacteria, fungi, and other natural systems disappear. This isn’t the case on the Zakarison farm, where they use regenerative strategies like no tilling, no pesticides, and no treated seeds (treated seeds have chemicals or other synthetic materials applied to the outside to boost their ability to grow). Selling regeneratively grown animal feed from their feed mill gives Ariel and Sheryl a chance to talk to hundreds of local farmers about the benefits of transitioning to regenerative agriculture.

“We sell our feed at a price that is typically lower than feed stores in our area so that we can help keep the small farm ecosystem and local food economy in our area healthy,” Zakarison says.

Plus, by using the intercropped grains for the feed mill, they can experiment more, Ariel says, because they don’t have to separate the grains after harvest or find separate markets for small amounts of different feeds—all palatable grains can go into their mill.

From Farm to City, Back to Farm

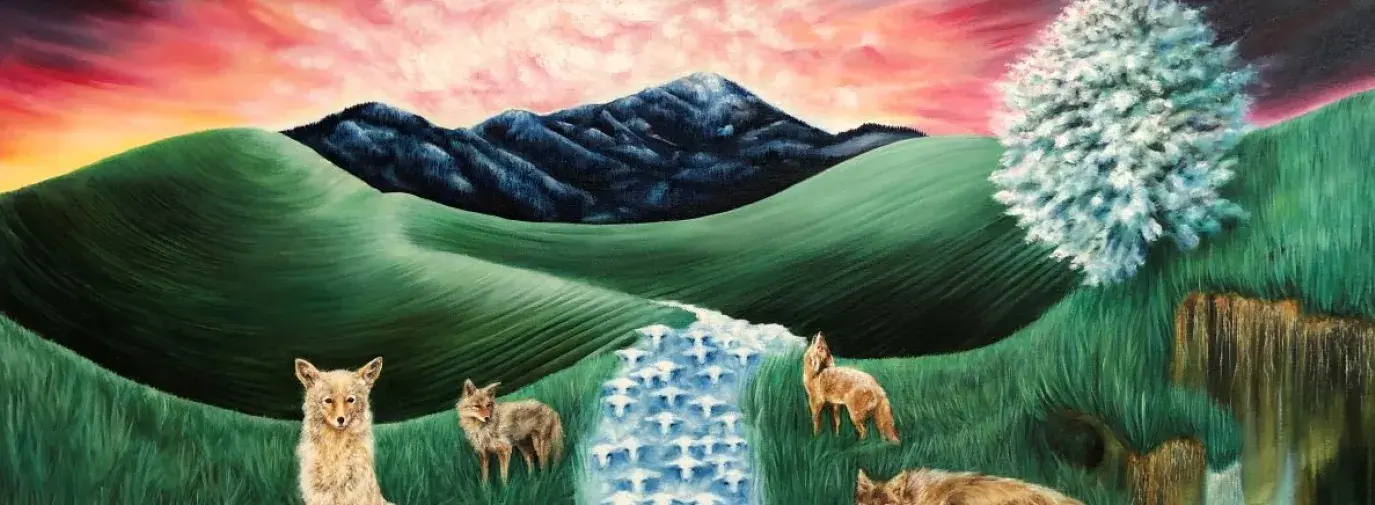

Ariel’s story is unique not just because she and her mother run a family farm together, but because she’s a farmer who nearly wasn’t. She went to school for fine arts, specifically painting and printmaking, first getting her bachelor’s degree at Western Washington University, nearly 400 miles from home. Then she followed her older sister, Shannon, almost 3,000 miles to New York City, where Ariel earned a Master of Fine Arts at Hunter College. She worked for the college for several years after graduating. Then she moved to Austin in 2020, but started doing multi-month stints back in Washington to help her parents with different aspects of farm management. In June 2021, she returned to the farm full-time.

But, she hasn’t abandoned her work as an artist—far from it. She keeps a studio on the farm and works in it, particularly during the winter months, when the needs of the farm are much fewer.

“Farming definitely has a huge influence in the artwork that I’m making,” Ariel says. “Both things are important to each other. The one keeps the other going at this point in my life, which is really neat.”

Though Ariel’s path to farming wasn’t direct, she comes from a long line of people who worked the same land she cares for each day. Her great-aunt ran away from home to The Palouse in the 1930s, and on finding a husband and farmland, sent for her struggling family to join her. The Zakarisons have been there ever since.

How Soil Can Heal

One of the reasons Ariel’s parents needed help on the farm is also a reason why they are transitioning to regenerative management. Eric Zakarison, Ariel’s father and Sheryl’s husband, is facing early onset Parkinson’s disease, making him unable to manage the farm he lived and worked on for his whole life. Ariel says this is a common diagnosis among farmers in their area; because of that, the family thinks pesticide use in the past and chemical exposure may be to blame for farmers’ illnesses. Indeed, a 2018 study by UCLA researchers found a link between those who used pesticides in their work and increased Parkinson’s risk, a link that continues to be studied.

One of the goals of regenerative transition is to reduce, or even eliminate, the use of chemicals on the land, resulting in healthier soil and healthier people. Two 2021 peer-reviewed studies, one of crustaceans and the other of frogs, showed pesticide exposure can have multi-generational toxicity, including negative effects on reproduction and metabolism.

Southeastern Washington, which is a participant in SCI’s Go-to-Market Pilot.

Sheryl studied agronomy in college at nearby Washington State University, where she met Eric. Ariel explains that Sheryl is the curious, environmentally motivated steward of the land who has led the farm’s transition into regenerative agriculture—which led them on the path of participating in the Soil Carbon Initiative’s Go-To-Market Pilot. Though they both studied farming, Sheryl and Eric had to trade off holding office jobs over the years, in order to get the family health insurance. Sheryl was curious about regenerative practices and once her children grew up, she was able to spend more time on the farm, convincing her husband and father-in-law to switch to no-till practices.

“She’s a fast learner and a voracious consumer of new information, especially around agriculture,” Ariel says. “She makes things really easy because she’s really excited about what we’re doing and she’s so involved and knowledgeable.”

With Ariel and Sheryl at the helm, the Zakarison farm is one of few led by a pair of women in conventional or regenerative agriculture in the US. Their passion for learning and bettering their land and community is evident, and contagious.

“[Sheryl] learned how to drive tractors and all this stuff first. I know that if she can do it, I’m sure I can do it. It’s kind of scary to learn how to do that at first, especially when you’re in your thirties learning a new trade,” Ariel says. “Now I love it. And I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”