I n the fields of America’s breadbasket and beyond, from California to Florida, Wisconsin to Louisiana, farmworkers rise with the sun to pick the fruits and vegetables you see in stores, or to pull weeds on organic farms. It’s hard work, but someone has to do it to keep food on America’s tables. And usually, that someone is an immigrant worker—nearly three-quarters of farmworkers are immigrants.

Ninety-five percent of US farmworkers are from Mexico, three percent from Central America, and the rest from other countries, according to the US Department of Labor. A little over half have legal immigration status. But it really doesn’t matter if they have papers or not—what they all have in common is that many are subjected to too-low wages, unsafe conditions, sexual assault and harassment, and more.

“Agriculture [in the US] was founded with a slave labor force. It was profitable because farms didn’t have to pay for labor. That created a culture and an understanding of what farm work is worth,” says Rosalinda Guillen, a former farmworker and executive director of Community to Community Development (C2C), a “community-led, eco-feminist organization” in Washington state that supports farmworkers as they advocate for their rights.

As a result, she says, farmworkers are almost invisible to the general public: “The invisibility of farmworkers helps justify the low wages, the lack of rights,” she says. “If we don’t exist, then we’re not counted when it comes to opportunities to have an equitable position in the community—unless it’s in a charity model. But we don’t need saving. We just need the same opportunities and rights as white people.”

In the tradition of legendary farmworker-rights activists Dolores Huerta and César Chávez, farmworkers are fighting on the ground for those rights.

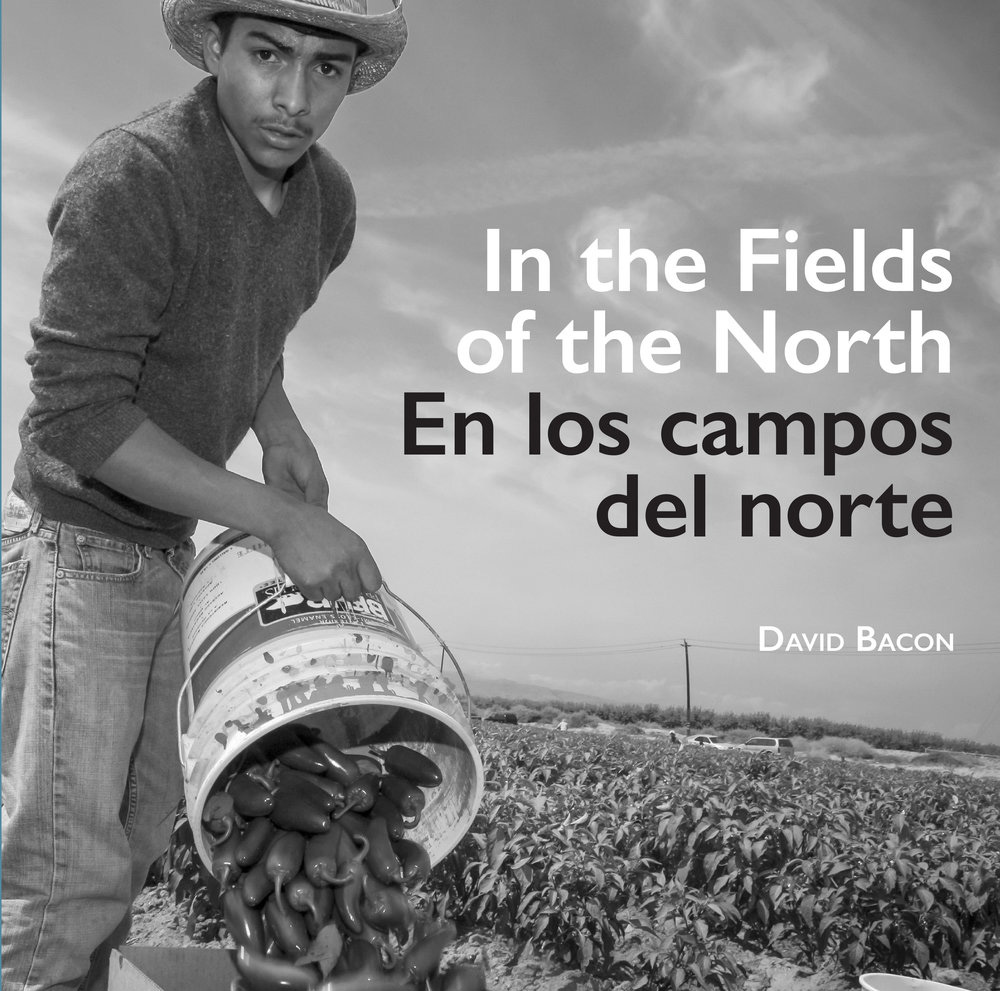

Caption for header photo: A boy picks strawberries in a crew of Mixtec migrants from Oaxaca. He says he’s 18 years old, a claim he’s been told to make if a photographer takes his picture. Photo by David Bacon.

Union Power

Guillen’s colleagues say she’s brilliant at seeing connections between multiple areas of food sustainability and the farmworker rights movement, so C2C works at the intersection of a broad array of issues: labor rights, environmental sustainability, food access, immigration, and more. It’s also fundraising to develop a training center to help farmworkers create farming co-ops.

“We’re providing support to farmworker leaders already out there trying to improve conditions for the community,” she says. “Farmworkers tell us what issues are important to them.”

As part of this work, C2C supports unions like the United Farmworkers of America (UFW), the nation’s largest farmworker union, and Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ), an independent union of over 500 Triqui-, Mixteco-, and Spanish-speaking workers at Sakuma Brothers Farms in Burlington, WA. These unions realized two prominent farmworker victories, with Guillen’s and C2C’s assistance.

The first occurred in 1995, when UFW won a union contract with Chateau Ste. Michelle wineries after an eight-year boycott over low wages, unpaid overtime, and a lack of collective bargaining rights for farmworkers in the company’s WA vineyards. At the time, Guillen was a UFW regional director in WA.

Today, Chateau Ste. Michelle has one of the best union contracts in the country, she says: “It’s union wine from vines to cork. The Teamsters have a [union] contract for the bottling component, and the vineyards have a contract with UFW.”

In 2013, FUJ farmworkers had been protesting working conditions at Sakuma Bros. for more than a decade, saying that they’d been subjected to wage theft, poverty-level pay, poor living conditions for migrant farmers, and worker abuse. Since they hadn’t made much progress, that year, the workers asked Driscoll Berries, a strawberry company that is Sakuma Bros. largest client, to use its clout to help them negotiate a union contract to address these abuses. When Driscoll refused to step in, FUJ called a state-wide boycott that soon turned into a national boycott.

After four years of boycotts, worker strikes and walkouts, and public pressure, Sakuma Bros. finally caved and signed a collective bargaining agreement in June 2017. The new agreement formally recognized the union; raised farmworker wages to $15 an hour; ensured that workers facing discipline would be treated fairly; arranged for regular meetings between Sakuma Bros. and union members; and agreed to develop a retirement plan for farmworkers by 2019. Guillen says that because of the union contract, things “are going really well” for farmworkers at Sakuma Bros. today.

C2C’s latest campaign supports farmworkers who come to the US on H2A guestworker visas, who say they’ve had to endure extremely oppressive working conditions, with no clear system for addressing abuses.

Under the program, farms in the US contract temporary farmworkers from Mexico to pick crops in their fields. Growers are supposed to provide housing, food, and travel under the program, says Guillen, but workers are being housed in terrible, barrack-like camps, and “exploitation at the farms is getting worse and worse every year.”

In 2017, 28-year-old farmworker Honesto Silva Ibarra died after falling ill on the job at Sarbanand Farms, a blueberry farm in Sumas, WA. While Sarbanand attributed his death to complications from diabetes, farmworkers and C2C claim Ibarra died from “extreme dehydration, malnutrition, and exhaustion.”

The Washington State Department of Labor and Industries ruled in February that no workplace or safety violations contributed to Ibarra’s death. However, the agency did cite Sarbanand for potentially up to $150,000 in fines for violations related to missed breaks and late meals for workers.

Farmworkers at Sarbanand held a protest in the days following Ibarra’s collapse and death, including a road march. Sarbanand fired about 65 of the protesting workers, according to the Lynden Tribune, a local newspaper.

“This year, we’re keeping an eye on Sarbanand,” says Guillen, noting that farmworkers could call for a boycott if conditions don’t improve. C2C is also calling for the H2A program to be modified or ended altogether.

Guillen says that the H2A program is being expanded under the Trump administration, even while states seem to lack the ability to ensure that guest farmworkers are safe on the job: “That’s their solution to farmers saying they don’t have a workforce [in the wake of the administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants], instead of humane immigration policies.”

Struggles on an Organic Farm

Organic certification does much to ensure a farm adheres to practices that are beneficial to the environment. But it does not address worker welfare. Even on organic farms, you’ll find farmworkers subjected to long hours, low pay, and abuse. Farmworkers are often fired when they speak up for their rights, but instead of stopping the fight there, some are taking farms to court.

In January 2017, two farmworkers, along with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Coalition (EEOC), filed a federal lawsuit accusing one of Florida’s largest organic farms of abuse.

The lawsuits alleged that Glaser Organic Farms, which grows organic produce for Whole Foods and others, stole tens of thousands in overtime pay from vulnerable workers who were undocumented or spoke limited English. The lawsuits also state that Glaser allowed supervisors to verbally abuse workers, and the farm fired workers who spoke up.

The EEOC lawsuit alleged that Glaser subjected Latin American kitchen employees to racial abuse and discrimination, including managers telling workers, “You Mexicans are ignorant,” or “Mexicans are lazy,” and calling Deborah Velasquez, a Guatemalan worker, things like “burra,” and “the chocolate one.” Velasquez was fired after she complained. Owner Stanley Glaser denied the charges.

In April 2017, Glaser settled the suit by agreeing to pay Velasquez and another kitchen worker $15,000, to implement an anti-discrimination policy, and to provide bilingual training to workers on their federal rights against discrimination and retaliation, overseen by an independent monitor.

Domestic Fair Trade

Many Green Americans know about fair trade, a system that helps farmworkers and other workers achieve fair, living wages, safe and healthy working conditions, collective bargaining, and more transparency. The system also encourages sustainable production. To date, fair trade has been primarily for workers in the developing world. But now, farmworkers are advancing fair trade in the US and Canada.

green tobacco sickness, an occupational health hazard. Photo by David Bacon.

The Domestic Fair Trade Association (DFTA) formed in 2008 as a membership organization to “unite the values of organic agriculture with the principles of fair trade” in the US and Canada. DFTA members include farmworkers, farmers, retailers, and processors. Five North American companies hold DFTA membership, including Maggie’s Organics, Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, Maple Valley Inc., Farmer Direct Co-op, and the Organically Grown Co.

“The concept of domestic fair trade was created because farmworker and small-producer organizations in the US and Canada, as well as organizations and businesses already working internationally on fair trade, found that many of the injustices occurring abroad were also happening right here [at home],” says Erika Inwald, DFTA’s national coordinator. “At the same time, organic certification was growing in the US, but this label largely did not address worker welfare. The domestic fair trade movement seeks to help the public not only choose food that is healthy and sustainable, but also just.”

Rosalinda Guillen and several farmworkers helped launch DFTA and develop the standards for domestic fair trade, which closely match standards in farmworker union contracts. Guillen says she has no idea why companies like Chateau Ste. Michelle don’t label their union food and beverage products, as she thinks it would add value in the way that fair trade labels do for coffee, tea, and other commodities.

DFTA is mainly an advocacy and policy organization. Inwald recommends looking for Food Justice Certification and the Equitable Food Initiative label. Both certification programs adhere to DFTA standards.

A Penny Per Pound

In the tomato fields of Immokalee, Florida, farmworkers, most of them Latin American and Haitian, pick tomatoes in the hot sun, many of which are destined for prominent fast-food chains like Wendy’s and Taco Bell. In 1993, realizing that their wage of 50 cents per 32-pound bucket hadn’t increased in 30 years, those farmworkers started the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) to collectively bargain for a raise and for an end to worker abuses on Florida farms.

Since then, the CIW created the groundbreaking Fair Food Program (FFP), which fast-food, food service, and grocery chains can join to ensure independent farm monitoring to prevent worker abuses, and to provide tomato pickers protections in cases of wage theft, sexual harassment, and forced overtime. Companies that sign onto the program also agree to a rate increase for farmworkers of a penny more per pound of tomatoes, which they say makes a big difference in farmworker earnings.

In 2005, Taco Bell became the first to sign the agreement. Others include Walmart, Burger King, Chipotle, Subway, McDonald’s, Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Stop & Shop, Giant, Aramark, and more.

Bottom-dweller Wendy’s continues to balk at signing the agreement. The CIW says that rather than joining, Wendy’s pulled out of the Florida tomato industry altogether. The company did release a new code of conduct for its suppliers, but the CIW says it lacks the enforcement and monitoring of the Fair Food Program, as well as the higher wage.

“[It’s] a perfect example of the failed, widely discredited approach to corporate social responsibility that is completely void of effective enforcement mechanisms to protect farmworkers’ human rights,” the group said in a statement.

#MeToo in the Fields

In February 2018, CIW also released a powerful new report, Now the Fear is Gone, detailing the plight of women farmworkers in the fields. Women encounter the same wage theft, abuse, and harsh working conditions as men, but they’re much more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault.

As the report states, “Over eighty percent of women farmworkers suffer sexual abuse and harassment. Assault and the most extreme forms of harassment are so common that many women consider it unavoidable. ... As one female worker succinctly described it, ‘You allow it, or they fire you.’”

Rather than just detailing the problem, the report offers a significant dose of hope in the form of a powerful solution: the CIW Fair Food Program.

In 2010, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission conducted a study of women farmworkers in California’s Central Valley. It found that the overall statistic remained true in the Valley: over 80 percent of the women had experienced some form of sexual harassment or assault.

“Hundreds, if not thousands, of women had to have sex with supervisors to get or keep jobs and/or put up with a constant barrage of grabbing and touching and propositions for sex by supervisors. A worker from Salinas, California, eventually told us that farm workers referred to one company’s field as the fil de calzón, or ‘field of panties,’ because so many supervisors raped women there,” states the EEOC study.

However, the Fair Food Program is making a real difference for farmworkers. Growers must abide by the FFP Code of Conduct, which has a zero-tolerance policy for sexual abuse. When a worker complains, the CIW says that “remediation is rapid, since growers must fix violations or lose the ability to sell their produce to Participating Buyers,” which are mainly large chains that make huge purchases. Those who violate any of the Code’s zero-tolerance stipulations find themselves terminated and barred from work on any FFP farms. The FFP provides education to terminated workers to help prevent future occurrences on other farms.

C2C’s Rosalinda Guillen says that union contracts provide similar protections for farmworkers against assault: “Contracts provide a legal mechanism for taking action—that workers trust. Nobody can be fired for complaining.”

In March, CIW farmworkers traveled to New York City to stage a five-day fast, calling on Wendy’s to help end sexual assault in the fields by joining the FFP.

“In the age of #MeToo, business leaders like [Wendy’s board chair] Nelson Peltz must use their power to end sexual violence in their companies’ supply chains, and not hide behind a shroud of silence that prevents survivors of sexual violence from obtaining justice,” said CIW farmworker Lupe Gonzalez in a statement. “Inaction in the face of a problem like sexual assault is unacceptable, but inaction in the face of a solution is unconscionable.”