We’re stronger together. United we stand, divided we fall.

When it comes to hardships, many of us take comfort and heartily believe these expressions. But when it comes to the economy, capitalism itself, it’s every person for themselves, let the free market decide, and pull yourself up by your bootstraps.

This kind of thinking costs us, a lot. Individualism and racism cost us a lot.

Measuring the Cost

The true cost of racism cannot be placed in a bank account—it costs real people every day. In cases like Emmett Till, Ahmaud Arbery, and Sandra Bland, it costs irreplaceable lives. At the other end of the spectrum, a subtly racist comment could ruin someone’s day and make them feel unsafe and unwanted. Safety and the right to the pursuit of happiness are profoundly valuable and yet intangible.

Yet, there are economic costs to racism for all of us. Several organizations and firms have tried to put a monetary price on what racist policy and society has cost in the economy. This is a cost not just for Black, brown, and other people of color who face it personally, but for every person in our country.

A February 2021 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco says the cost of racial and gender inequity on the gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of the economy) is $2.6 trillion, and that’s just for 2019. Over the last 30 years, gender and racial gaps have created greater and greater losses in the US GDP that add up to approximately $71 trillion.

A 2020 report from analysts at Citi Bank calculated that if the US had closed the Black-white economic gap by the year 2000, the US economy would be worth $16 trillion more than it is now. That could have included $2.7 trillion in incomes, 6.1 million jobs created through investment in Black entrepreneurs, and 770,000 potential Black homeowners, with home ownership being a path to generational wealth over centuries.

Why Can’t We Close the Gap?

Workers Pitted Against Each Other

The gaps in pay and wealth stay open because racist, capitalist culture has Americans bathing in the lie that the economy is a zero-sum game—if people who are different from “us” are gaining, “our people” must be losing. White people are fed this idea by “divide-and-conquer” politicians and companies who benefit from upholding the belief, which can come from either side of the aisle, according to a 2019 social psychology study in Science Advances.

Economist and author Heather McGhee shared a story in her 2019 TED talk, about visiting an auto factory in Mississippi where workers were trying to form a union. The benefits—higher pay, a pension, and better healthcare—would have helped everyone, regardless of race. McGhee heard from white workers she interviewed that they planned to vote against the union if the Black workers were for it. The Black workers told her the same. Both groups believed that if someone that didn’t look like them was lifted up, then they would be left behind or even lowered. The union vote failed.

McGhee noted the importance of not blaming factory workers for their views. Companies keep money in their accounts when union votes fail. Indeed, sowing racial discord is an anti-union tactic companies may use purposefully or subliminally.

“I’m more interested in holding accountable people who are selling racist ideas for their profit than those who are desperate enough to buy it,” McGhee said.

For the people, Black and white, who didn’t get to join the union, they and their families lost out on higher wages, which would be good for the local economy, giving them more spending money, quality healthcare, and more. But what about for the rest of the country, outside that community?

“To a large degree, the story of the hollowing out of the American working class is a story of the Southern economy, with its deep legacy of exploitative labor and divide-and-conquer tactics, going national,” McGhee wrote in her book, The Sum of Us. In that book, McGhee uncovers the hidden economic costs of racism to the entire population.

Whether or not we choose to acknowledge it, our society’s tendency to “ladder” individuals is what keeps equitable policies back, says Amanda N. Jackson, economic justice campaigns director at Color of Change, a civil rights organization that uses online organizing to uplift Black communities.

“Folks need to feel that they are a rung higher than the person that is not them, or create a scenario where people are ‘below’ them,” Jackson says. “The government had racist redlining laws on the books nearing the 1970s to ensure that a whole class of folks, Black people, could not have home ownership, and therefore wealth, that was on par with white society.”

Education Alone is Not the Fix

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco report shows that disparities in labor market outcomes, like earnings and ability to get a job, have persisted “despite changes in laws, policies, and programs meant to remove barriers and prevent discriminatory practices.” It even says that the gaps cannot be explained by measures of talent or skill—meaning race and gender mean more to your job outlook than your degree.

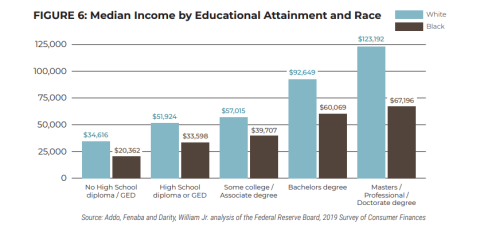

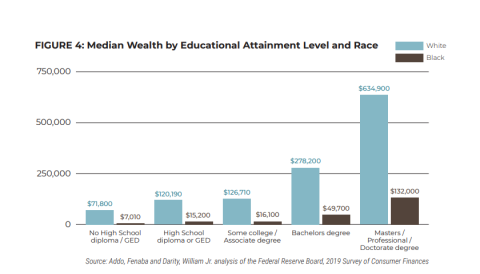

Pervasive anti-Black stereotypes might cause people to think—if more people of color and women got degrees, then they would be able to get better jobs. But the data shows that’s not true. According to 2021 report from think tank The Insight Center, education might be increasing the earning power for white people, but only increasing debt for Black families. Black households with advanced degrees have about half the wealth as a white household with a bachelor’s degree according to that report.

Jhumpa Bhattacharya, vice president for programs and strategy at the Insight Center, says that paradoxically, the more education that Black people obtain, the bigger the gap in wealth becomes, because they are forced deeper into debt. For example, median wealth held by a white person with a bachelor’s degree is $278,200, whereas for a Black person that figure is $49,700. For a white person with a master’s or doctorate, median wealth is $634,900 where a Black person in the same circumstances median wealth is only $132,000, still less than half of a white person with a bachelor’s degree.

“The system was built for you to stay in a certain place and for particularly white men to be able to move forward, so we cannot expect the same solutions that helped white folks gain wealth to do the same for Black and brown people. We actually have to change the system,” Bhattacharya told a group of philanthropists in a talk for the Asset Funders Network.

How do we Imagine and Implement Solutions?

Investing in People is a Proven Solution

Bhattacharya explains when looking for solutions to an economic gap like this, the people are the economy. When you balance a household budget, what you spend must be covered by your income that month—but that’s not how an effective government invests in its people, she explains. Bhattacharya says a government that’s by the people and for the people should be investing in people, not always looking for direct revenue to make it up.

“Let’s say you invest in the child tax credit [from the Build Back Better bill]. What does that do? It gives people money. That’s money going out the door, but it’s also money that people can spend in the economy,” Bhattacharya says. “It allows people to live healthy lives. That’s the way we should be thinking about revenue and the economy.”

The child tax credit was a payment sent by the government to help cover the cost of raising children, which is a common benefit citizens of other wealthy countries receive. This was part of the American Rescue Plan for COVID-19 relief, increasing and expanding a previous benefit, as well as making it monthly. The benefit gave families a dependable source of income and closed a loophole excluding half of all Black and Hispanic children from fully benefiting because their families earned too little income, according to NPR. The child tax credit under the American Rescue Plan cut child poverty by roughly a third and cut food insufficiency by 26%.

Another example of investing in the people was a coalitional campaign Bhattacharya and her colleagues at the Insight Center helped drive, that led to the passage of The Families Over Fees Act in California in September 2020, which forgave $16 billion in criminal legal fees and fines, such as arrest fees, parole fees, and jurisdictional transfer fees, among 20 others, debt that was mostly held by Black people. In theory, these fees are billed to fund the legal system but end up acting as their own form of punishment to people charged of crimes as they pursue justice and to those released from incarceration.

“We talked about the impact it really has on people—the mental stress that folks have to deal with when their wages are being garnished to pay off these really unjust debts,” Bhattacharya says. “Think about balancing a budget to bring into government coffers by charging a surcharge on mostly Black and brown people who are struggling to make ends meet anyway.”

We cannot expect the same solutions that helped white folks gain wealth to do the same for Black and brown people. We actually have to change the system.

—Jhumpa Bhattacharya, Insight Center

Eliminating these debts is an important step in dismantling centuries of racist economic practices. Unfortunately, many states still charge fees that end up costing Black and brown people more. Changes in narrative and information about these successes create shifts toward justice. We need large and small shifts to move us closer to closing the wealth gap and ending economic oppression.

Build on the Social Shifts of the Pandemic

The last two years have been game-changing in work that seeks to close gaps and end economic injustice. The pandemic and the summer of Black Lives Matter protests following the 2020 murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others, moved the needle on social justice movements. According to experts across sectors, white people became more aware of social injustices, from violent policing to Black people dying at disproportionate rates from COVID-19.

For example, James Malone, chief financial and diversity officer at Community Capital Management (CCM) {GBN}, says 2020 was a tipping point for many investors, who became more willing to put more money toward impact investing for Black and brown communities. The Land Back movement also gained traction—which is a win for social justice and the economy. In so many ways, imaginative solutions to social inequality will benefit all of us.

Jackson says we need to make sure these changes persist in the coming years.

“Many Black households and households of color are still struggling to rebuild—normal was never a context to apply to these communities,” Jackson says. “If we aren’t grounding economic injustice now in the pandemic, I think it just becomes a greater challenge to do so.”

Systemic issues, economic racism, and individualism costs so much more than money—it costs people the vast possibilities their futures could hold. That’s not the status quo we want to continue; social change is possible if we continue the momentum. Fighting for justice for all communities in policies and opening our minds to unlearning beliefs can propel us forward to a world built on thriving communities and care. Our country is held back by racism in countless systems—there is no wrong place to start dismantling it.

We can do it for the equitable chance at a bright future and well-being. Because united, we stand. Together, we rise. ✺