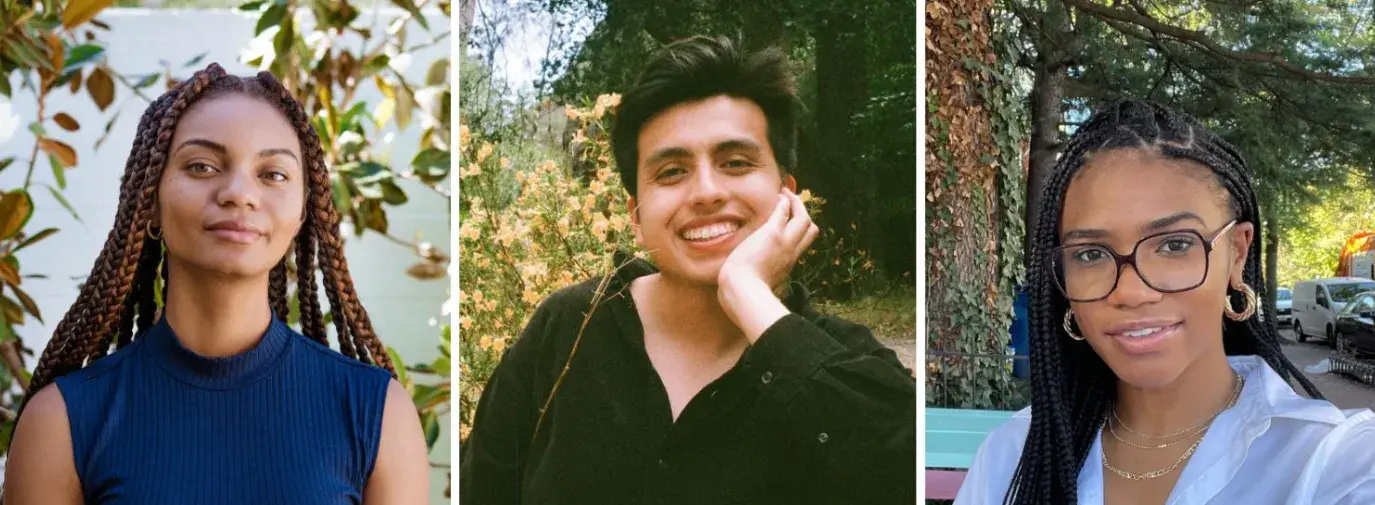

“The Atlantic Slave Trade permanently altered shark migration in the Atlantic Ocean,” Arielle V. King, 23, begins her TikTok.

The video, viewed nearly 600,000 times on her account @ariellevking, explains how sharks following the slave ships, feasting on the Black bodies thrown overboard, forever changed their movements.

On Instagram, Isaias Hernandez, aka @QueerBrownVegan, 25, posts about everything from foraging mushrooms to divesting from fossil fuels. Leah Thomas, 27, is @greengirlleah on Instagram, where she educates on topics like zero waste and promotes her organization Intersectional Environmentalist.

With knowledge gleaned from childhoods spent online, young people have harnessed the immense power of the digital world—and proven social media is more than its faults.

Don’t Underestimate Them

Despite confidence and passion for these causes, ageism is often an ugly truth for young people—especially those who use their voices publicly.

According to the UN’s 2021 Global Report on Ageism, discrimination and stereotyping of young people “manifests across a range of institutions including the workplace, the legal system and politics.”

King has experienced ageism, having gone to college at 16 and being viewed as the “little kid” in workplaces.

Now, in her role as an environmental justice staff attorney at the Environmental Law Institute, she finds spaces where her contributions are appreciated.

“I would never limit myself to only listening to people who are older than me—it would shut out so much learning,” she adds.

There are times when it’s not possible to choose a safe space, however. According to the UN report, in the political world, older people tend to dismiss the voices of youth and children due to doubting the “authenticity” of their perspectives.

It makes little sense when you realize Millennials are the generation of 9/11 and the 2008 housing crisis, and Gen Z-ers are the generation of mass shootings, climate change, and covid-19. Their life experiences uniquely prime them to speak out.

Thomas explains another reason to respect and listen to younger voices.

“Children are forfeiting some of their childhood because they care so much,” she says, referring to students’ decisions to participate in protests like Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for the Future. “People don’t realize kids are missing school and life moments because they’re scared and so deeply want a future where they’re safe.”

Fighting for a Collective Good

These experiences are compounded for marginalized voices, like communities of color, women, LGBTQ+ people, and others.

“We have been normalized and indoctrinated by an economic system to believe we deserve to live in a poisoned environment,” Hernandez says.

Even social media—an ideally democratic space where anyone anywhere can create an account—bends to the wills of oppressive institutions.

Tired of a sustainability space dominated by white, wealthy voices talking about throwing money at a $300 sustainable dress or an electric car, Thomas took matters into her own hands. She created the Intersectional Environmentalist, a “climate justice community and resource hub centering BIPOC and historically under-amplified voices.”

“There’s a lot of Black women who have been doing this work before me,” Thomas explains. “There’s no reason this attention needs to be going one person, it needs to go to a collective good.”

While reflecting on a viral post she made in 2020 that read “Environmentalists for Black Lives,” Thomas described feeling “afraid” because in most environmental spaces she inhabited, she was “one of only a few Black faces.” The virality of her post revealed not only the message’s resonance, but the need to do the work and make environmental spaces more diverse.

Accessible Content for a Curious Audience

According to Pew, a majority of adults in the US use Facebook and Instagram daily, and nearly half use Twitter every day.

An added bonus to using social media to share their message, according to King? “There’s no barrier for entry. Especially in the US, where we have to pay for higher education, having access to people sharing this information for free opens up opportunities.”

This learning can not only co-exist with often-inaccessible academic spaces, but also transform them into something accessible, inclusive, and truthful. Historically, communities of color face more barriers getting into higher education—from attending poorly-funded high schools to the attacks on and limits of programs like affirmative action. Denying people the chance to learn—in a society where higher education is often deemed necessary—ensures they will not have a seat at the table, despite their lived experiences, knowledge, and ideas.

King, Hernandez, and Thomas all agree environmental justice can be for everyone, especially those disproportionately affected by climate disasters, like Black communities in the South and Indigenous people fighting for clean water and their land.

“These terms don’t have to be as complex as the ivory tower has made them,” King says.

The ease of social media can also account for people’s learning levels and lack of education access.

“A lot of people respond to social media posts: ‘You’re just synthesizing the work I’ve been doing for years, people should read a book.’” Thomas says. “I do believe in reading books, but [some audiences are] more likely to read or watch this post than that dense book with words I can’t even understand with my degree.”

I do believe in reading books, but [some audiences are] more likely to read or watch this post than that dense book with words I can’t even understand with my degree.”

—Leah Thomas,

Intersectional Environmentalist

It’s hardly the first time introducing big concepts to different audiences. Bill Nye, anyone? Encouraging and advocating for education is to see someone’s potential.

By its nature, social media fosters community and learning via engagement (comments, re-sharing, “dueting” on TikTok, etc.) Features like events and groups on Facebook make it easy to plan actions and collaborate. Communication is simple on social media, making vital information—a protest location, talking points—accessible, which in turn encourages action.

As Advocates for Youth states in its Youth Activist Toolkit: “You will not win your campaign because of social media, but you can’t win without it.”

In June, King spoke on climate justice at a virtual, international Model UN climate conference for middle and high school students.

“Some of the things they were bringing up and asking me [like suggestions for holding corporate polluters accountable] I hadn’t heard any of those comments in my classroom discussions or considered those ideas. It’s really inspiring.”