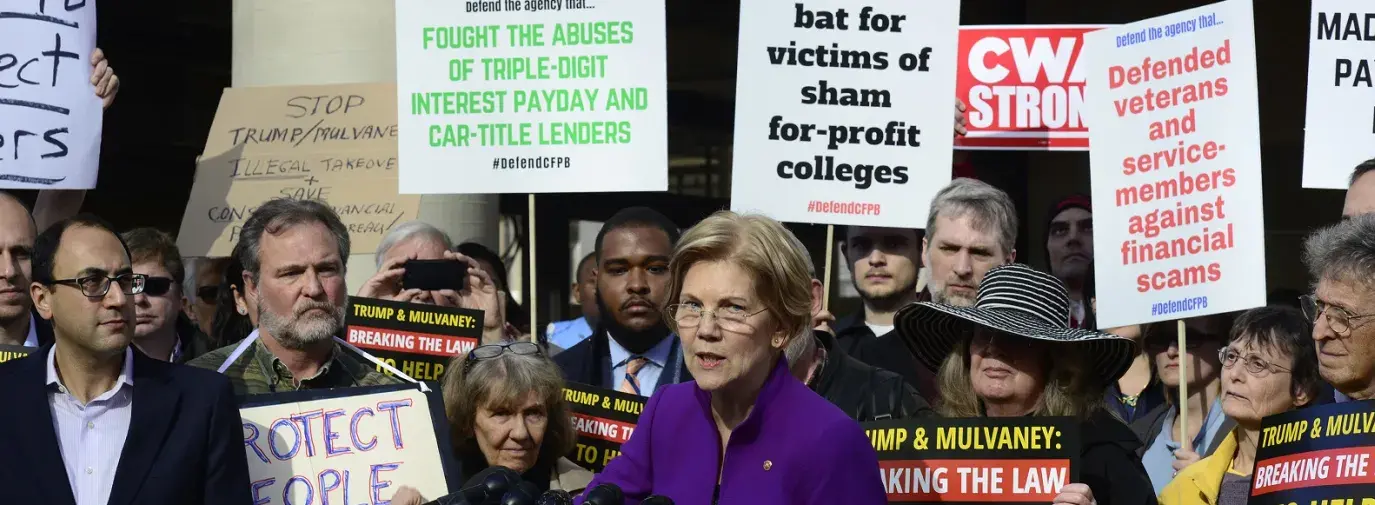

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Democrats in Congress worked with the Obama administration to pass the Dodd-Frank Act, which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), and put several key financial protections on the legal books. The law aimed to prevent future financial crises and to protect vulnerable Americans from Wall Street and mega-bank excesses and from predatory financial practices.

The CFPB’s first director, Richard Cordray, resigned shortly after Trump’s election, after which the president appointed vocal anti-CFPB critic Mick Mulvaney as acting director.

In 2017, the CFPB survived a 2017 bill called the Financial CHOICE Act (HR 10), which would have dismantled the CFPB, decimated Dodd-Frank financial regulations, and limited the ability of shareholders to engage with corporations.

Despite the fact that Congress was not successful in passing the bill, the Trump administration has been successful in slowing the agency’s work to molasses. The Washington Post reported that publicly announced enforcement actions by the bureau have dropped about 75 percent from average in recent years, while consumer complaints have risen to new highs.

From December 2017 to December 2018, the agency’s workforce dropped by 129 employees. Seth Frotman was one of them. Before his resignation in August 2018, he was the CFPB’s assistant director and student loan ombudsman.

“The bureau is forcing hundreds of staff to sit on their hands while millions of Americans suffer from predatory practices happening right under its nose,” said Frotman to the Washington Post.

In December 2018, Kathy Kraninger was approved in a 50-49 Senate vote to head the agency for a five-year term. Kraninger has put a focus on “consumer education,” which may sound inocuous enough, but not when the agency’s stated mission is consumer protection, which includes holding financial institutions accountable for bad actions, says Linda Jun, senior policy counsel at Americans for Financial Reform (AFR).

Since Kraninger took over the CFPB, she has largely kept the agency on the same track as Mulvaney had it on, says Jun. The only major difference is she’s not actively trying to dismantle it. What has she gotten done? Jun notes three policies Kraninger has affected:

1. The Payday Lenders Rule

This rule was finalized in 2017 after five years of research, discussion, and public comment. The rule states that payday lenders must consider whether lendees have the ability to pay back their loans, an action that would reduce predatory lending. Kraninger has proposed a delay in the compliance date of the rule and to repeal the rule altogether. In June 2019, Kraninger succeeded in delaying the rule's compliance date until November 2020.

2. The Debt Collection Rule

This rule is quite long (538 typed pages, Jun notes), but a main concern of Jun and AFR is that the rule allows violations of consumer privacy by allowing debt collectors to leave confusing messages via text, email, and direct message on social media without recipients’ consent. This makes debt collection even more intrusive than typical phone calls and may cost money to lendees (for example, if you have a prepaid plan where you have to pay per text). Jun is a lawyer and it has even taken her weeks to parse through the complicated language.

3. The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

This act is used to collect data on mortgages, which helps identify patterns that might be useful for holding banks accountable for bad practices, including discriminatory practices. The CFPB is raising the threshold for reporting, meaning that more financial institutions will be exempt from reporting data, which means less will be collected overall and patterns will be harder to identify.

“The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has its mission in its name. And there are a lot of questions of whether it’s actually pursuing that mission, versus protecting lenders and financial institutions,” says Jun. “When the CFPB is doing its job, we see bad behavior is curtailed and people are protected. The question is, is that happening now?”

What You Can Do

For a regular person (or “consumer” as we’re known to the CFPB), it can be hard to know what to do to help a faraway agency, even if you think the work they do has the potential to do good (not unlike the EPA these days).

Jun reminds us that we all participate in financial products, and in that way are the consumers that the agency was designed to protect. You’re a consumer if you have a credit card, have student debt, take out a loan, are harassed by debt collectors, have a mortgage, or open a new account. You can take action by reporting problems you may have with those products and the companies that sold those products to you.

“It’s an important piece to share your story, whether that’s with advocacy organizations, or directly with your elected officials, or the regulators at the CFPB or anywhere else,” says Jun. “There’s value in bringing things to light, which helps people identify patterns and helps elevate these issues and show that these are real things that happen to real people.”

You can also tell your elected officials your story with debt, loans, or bad-actor banks. Whether or not a bill is on the table, it’s important that they know their constituents care about the the CFPB.

“The reason this stuff matters is that we want the average person, no matter who they are, whether they live in the countryside or the city, when they go get a loan or get a credit card, that the process is fair, and you know what you’re getting,” says Jun. “That’s what we’re advocating for. The details are confusing. A lot of groups are doing our best to distill what’s happening into more readable resources so real people can engage.”

To find resources on different financial topics or submit a complaint to the CFPB, go to consumerfinance.gov.

To keep up to date on CFPB and other financial news from Americans for Financial Reform, and find more financial resources, go to ourfinancialsecurity.org.

To leave your bad-acting bank and find a community bank or credit union in your area, go to greenamerica.org/getabetterbank.