Written by Peter Watts, a recently retired science educator who integrated gardening, land-use, and other environmental lessons into his classes for three decades at Riverside Middle School. Today, he consults on establishing pollinator habitats, re-wilding lands, and environmental science education with his company PhenoCulture Wisconsin, LLC.

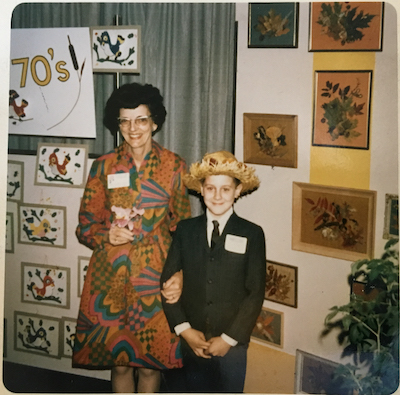

Mrs. Morton pushed up her dark cat-eye glasses and announced the upcoming assignment, asking our fourth-grade class to collect at least four different autumn leaves for a project. The class was abuzz with enthusiasm, but I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to do this because our city street was lined with a monoculture of majestic elms (which were completely decimated by Dutch Elm Disease a few years later).

Instead, my parents took me to a nearby park. The exuberant vibrance of autumn awakened my soul as I looked up at the blazing red sugar maple, golden white birch, electric ruby purple ash, and yellow-orange red oak. I ran along the mowed grass, embracing the trunks and feeling the bark of each tree, collecting leaves, clutching them protectively to my chest. Back at school, we pressed the leaves and mounted them on burlap in a wood picture frame.

Later that winter of 1969, we planted marigolds and in early spring we germinated seeds and grew tomatoes and zinnias, nurturing them until we brought them home. I was allowed a small garden plot in our tiny backyard to grow my treasured plants. I was so proud of my little garden.

Fourth grade with Mrs. Morton changed me forever—I give her credit for awakening the part of me that craves the outdoors and is heavily influenced by the changing seasons. It is because of her that I have taken the proud path of self-sufficiency, becoming an activist, environmentalist, and science educator.

Building a Modern School Climate Victory Garden

Fast forward to early 2014, when my school was awarded a $4,000 grant from the United States Department of Agriculture and Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction to build a garden. Exciting as that was, it took convincing to get our superintendent, buildings and grounds manager, and business manager on board. They wanted the garden in an obscure location across the street where it wouldn’t be an eyesore; I wanted high visibility, closer to classrooms with lots of sun and access to water.

I invited all three of them to physically come to the frozen, snow-covered middle school site in February, where I enthusiastically walked them through my vision, step-by-step. I assured them that this would not become the weed infestation that some worried about. This garden would be an extension of the science classroom and an important resource—and in the end they couldn’t deny that the project was worth a try.

Our district nutritional services manager was excited about the project and its potential to serve food grown by students, and she sent over the common-sense food safety requirements. We agreed on suitable crops that fit within the restrictive logistics of a modern middle school kitchen. I sent emails to parents, typed up a school newsletter article, and contacted our local newspaper. Hearing about our garden, area businesses gave us more funding even before we broke ground.

We started saving cardboard boxes, ordering seeds, designing the 1,000 square foot garden, and building a seed-starting rack. Over the next month, I made lots of visits to local stores, making connections, networking, and compiling a list of materials that were within budget. Our city street department was also greatly supportive, offering to deliver wood chips for the paths at no cost.

On April 12, 2014, fifty students, parents, and friends showed up with their own tools, ready to build the sixteen beautiful cedar raised beds for my seventh-grade students to plant and grow food. That first spring was bitterly cold and wet, so plants had to be nurtured inside to start. In early May, we had over twenty cubic yards of soil delivered. Students spent science classes outside filling boxes and laying out paths, gridding the boxes, and planting tomatoes, peppers, broccoli, eggplant, potatoes, onions, celery, and cauliflower.

Today the Riverside Middle School Garden has grown to 7,000 square feet with a 1,150-gallon roof water collection tank, 16’x32’ hoop house, 10’x20’ pergola with 10 Leopold benches, and a 12’x8’ shed—all built with grants amounting to over $30,000.

A school garden provides so many lessons about biology, math, geology, chemistry, writing, climate change, sustainability, and regenerative agriculture. I never had to explain why we weren’t inside doing worksheets and reading textbooks. Anyone observing the chaos would know instantly that these kids were getting a real hands-on, minds-on education!

Benefits Beyond the School Yard

Food insecurity can be eradicated through education, compassion, and activism. During the summer, our school-grown fresh food is delivered to community elders and at least 40 meals-on-wheels each week. Students also built a produce stand to set out free fall harvests of squash. No one should go hungry in our community, another important lesson for my students.

What we’ve accomplished with the Riverside Middle School Garden is a microcosm of what the Climate Victory Gardening movement is working to achieve. Through education and guidance, everyone can learn how to be more self-sufficient and connected with the earth. Gardening is an active process that teaches us about soil, phenology, the nitrogen cycle, weather, and climate. It also teaches us the importance of community and hard work.

As one of my heroes Ron Finley says, “Gardening is the most therapeutic and defiant act you can do, especially in the inner city.” The most effective catalyst to spark community in your school while growing one’s own food? I believe it’s teachers like Mrs. Morton.

Read more inspiring Climate Victory Garden stories and tips.