The victory gardening movement of the 1940s was a time for grassroots collective action—when households across the country grew incredible amounts of food. It was also a time when war was used to justify extreme xenophobia and oppression of non-white Americans.

Green America’s Climate Victory Gardening campaign strives to reclaim the good from this movement, but we can’t do that without addressing the hurt and racism that Japanese Americans experienced directly related to the WWII victory gardens during this terrible time in our country’s history.

Racism Leads to the Incarceration of Japanese Americans

While many point to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor as the start of xenophobia towards Japanese Americans, racism and injustice existed long before WWII.

First-generation Japanese immigrants were barred from becoming citizens and faced discrimination in labor markets and land ownership from the moment they arrived in the United States. Many settled in the states along the West Coast and farming was the only occupation available to them. In 1934, one third of Los Angeles’s Japanese American workforce farmed and gardened.

Thanks to generations of farming knowledge from Japan, these workers were wildly successful at growing food in the American west. Second-generation Japanese Americans were able to become citizens and began owning small farms and they quickly became an important part of US agriculture. Data from the period show that Japanese American farms were more productive and profitable than other farms. In 1940, they produced more than 10 percent of California’s food by value even though they held less than four percent of farmlands.

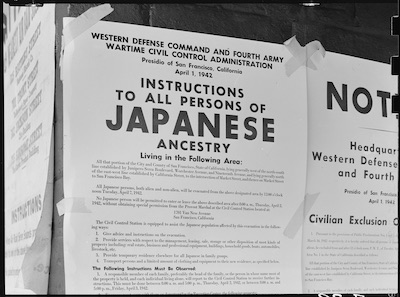

In 1941, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor, leading to the United States’ formal entry into WWII. The existing racism towards Japanese Americans was intensified by fear and war propaganda. The next year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which called for the forceful removal of over 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent from the west coast to concentration camps farther inland.

Two thirds of those in camps were American citizens. There were no formal charges against these prisoners and no significant convictions of any Japanese Americans for espionage during the entire war. This was incarceration due to ethnicity alone.

Injustice towards Japanese Americans was compounded by the action of white-owned corporate agribusinesses, which saw the opportunity to take over these family farms. Lobbying from industrial agriculture with “competing economic interests” targeted and forcibly removed successful Japanese American growers from their farmlands.

We understand that terms like “concentration camp” and “incarceration” might not match words you’ve heard used in the past, like “internment” and “relocation.” If you’re wondering about our word choice this article is for you.

Japanese Gardens in Incarceration Camps

Japanese Americans lost their homes, their businesses, their rights, and in some cases their lives. They were moved to incarceration camps that were little more than barren lands with barracks surrounded by guard towers and barbed wire. In fact, the land chosen for the camps was intentionally poor, because the government hoped that their new inmates would use their farming expertise to improve the land with enormous agricultural projects. The camps were isolated; sickness, beatings, and death were everyday experiences.

This is not the scene that comes to mind when most Americans think of victory gardens, but these camps were home to thousands of individual gardens that played an important role somewhere between horticultural therapy and survival. Gardens in the camps served cultural and health purposes, acted as a buffer against psychological trauma, and represented an attempt to re-create community in these harsh new environments. There were beautiful ornamental gardens and gardens that grew traditional Japanese vegetables to supplement terrible meals in the camps.

Camp gardens were also a form of resistance. Many of the inmates faced complex feelings around American patriotism, the injustices of Executive Order 9066, and betrayal by their white neighbors. Gardens were an opportunity to physically rebuild their community but, for some, they were also considered subversive symbols of non-compliance, resistance against confinement, and even appropriation of the War Relocation Authority’s land. Gardening often required illegal acts to acquire materials and became highly politicized in some of the camps.

Government Promotes Household Victory Gardens

Outside the camps, the US government aggressively promoted victory gardening at the household level. Fearing food shortages, the need for such a huge civilian mobilization was often attributed to farmers becoming soldiers, war allies relying on US production, and feeding troops. Gardening was marketed as family fun, healthy recreation, and patriotic.

What few knew then and even fewer know now, is that rationing programs and food shortages were largely due to the incarceration of many of the United States’ most productive farmers. When Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their land, food supplies plummeted and prices skyrocketed. In 1942, Japanese American-owned farms were expected to provide half of the canning tomatoes and 95% of all fresh snap beans for the war effort. They were also the primary growers of strawberries for civilian consumption.

The colorful, upbeat, whitewashed victory gardening posters do nothing to hint at the over 6,100 farms that were taken from Japanese Americans (estimated to be worth over $1.3b today). They do nothing to show the forced labor of German prisoners of war and Japanese internees, and they ignore the fact that the government had to import thousands of Mexican workers to keep the United States food supply stable.

Reclaiming Victory Gardens to Face Today’s Crises

What do we do with this deeply troubling history?

First, we can acknowledge that this history is not behind us. Stigma of the incarceration camps remains, and reparations fall short. The US didn’t apologize or offer restitution to impacted Japanese Americans until 1988—too little too late. In general, the US doesn’t have a great track record for delivering reparations to groups who’ve been forced from their lands and into forced labor, including enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples. Racism persists in the face of climate and global health crises, as marginalized communities are hit hardest and—again—as anti-Asian racism spreads, but this time amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

We can also reclaim what was good about the victory gardening movement of the 1940s, when 20 million people took action to feed their families and communities in uncertain times. We can again tap into therapeutic potential of gardening. And, this time, we can garden in a way that’s good for the planet (unlike the chemical-heavy methods used during the 1940s).

The victory garden movement was a top-down model, with the government driving action. Today, we’re seeing incredible amounts of grassroots action around growing food that directly opposes the systems that reinforce oppression, the industrialization of our food system, and centralization of power. Across the country, people are building Climate Victory Gardens that bring communities together and provide nourishing food to people who live in food-insecure areas—those experiencing food apartheid and facing racism.

We need everyone to be part of the climate solution and easing the impacts of the pandemic. Gardens have a role in the future we’re striving to create; racism does not.

Here are some great organizations addressing anti-Asian backlash today:

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice

- Asian Pacific Environmental Network

- Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and Chinese for Affirmative Action have launched an incident report for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders experiencing microaggressions, racial profiling, hate incidents, and hate violence

Here are some organizations working to ensure gardening is available to all:

It’s important that Americans work together to make sustainable gardening and agriculture a viable activity for all groups and communities—one that honors the wisdom and connection to the land of diverse peoples.